Unable to complete an in-person placement as planned in the summer of 2020 as part of the Textile Conservation programme at the University of Glasgow, I was fortunate to instead complete a virtual placement with Zenzie Tinker Conservation (ZTC).

ZTC Ltd assigned me a research project; to produce a testable method of using clay poultices and regenerated cellulose membranes to clean delicate historic textiles which are subject to dye bleed. This research was based on tests done a year previously by Rachel Rhodes, a freelance textile conservator at ZTC. The aim of my project was to develop the method further in collaboration with Rachel. The focus was on specific materials used and developed in France by Thalia Bouzid during her Master’s thesis. Thalia developed the clay poultice method using montmorillonite clay, deionised water as the solvent and regenerated cellulose membrane as the barrier layer to treat very fragile archaeological textiles.

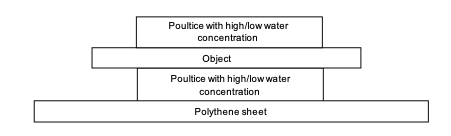

Key outcomes of the project were that regenerated cellulose membranes are an effective barrier layer at allowing the slow release of moisture into a textile and that one can humidify the samples slowly and safely. Rather than the poultice only being applied on top of the object; a high concentration of clay should be used in conjunction with a low concentration poultice above and below the object or vice versa (see fig 1 ). This creates the direction of low water to high water concentration flow.

Still keen to gain practical experience working in a conservation studio, I was lucky enough to be an intern at ZTC studio for three weeks between 29 March – 16 April 2021.

Practical experience is a very important part of training to be a textile conservator, developing conservation skills and building confidence in decision making. Missing out on this opportunity due to the Covid-19 pandemic was a disappointment to me and my classmates. Zenzie and I had been discussing the possibility of me completing an in-person placement as a follow on from my virtual placement but with the uncertainty caused by the first and second waves of the pandemic, it had not been possible. As we moved into spring 2021 and the horizon of restrictions being eased, we managed to confirm dates. The excitement of attending the placement in-person was also filled with apprehension of whether I would be able to complete tasks assigned to me. Being such a short placement, rather than focus on the treatment of one object, I helped out with a range of projects, both in the studio and on-site (see fig 2, site work at a corporate client’s offices in London).

My first few days were spent surface cleaning some contemporary tapestries (see fig 1) designed and woven by Marta Rogoyska. These bold and striking tapestries were not visibly dirty but had experienced some slight insect activity and, due to them being hung in a large public office foyer in London, required frequent cleaning to stabilise them. I initially surface cleaned the tapestries with a low suction vacuum cleaner, followed by cleaning with smoke sponges, and a last clean with a low suction vacuum cleaner. The practical nature of conservation work is something that has always drawn me to be a textile conservator. Although physically demanding, the placement confirmed how rewarding I find this type of work, while also making my realise that being a bit fitter might help me cope with the demands of conservation! Cleaning the tapestries did not make a significant visual difference but the smoke sponges showed how much dirt was being removed from surface cleaning, demonstrating how quickly textiles become soiled and that soiling is not always as visible as we might think. Cleaning tests are always important to accurately assess whether a textile needs surface cleaning.

© Zenzie Tinker Conservation Ltd

Cleaning the tapestries was followed by condition assessing a tapestry and a Chinese silk embroidery, both which were large textile pieces and much larger than anything I had worked on. The ZTC team were amused when I commented on the textiles large size – this was not large compared to projects they are often commissioned to work on. Size, as I learnt, is relative. As we mainly treat textile objects independently on the Textile Conservation programme, we work on objects that are manageable to be treated by one person and within a certain time frame. Although we learn to handle and manoeuvre large textiles, it is not something we practice regularly. Subsequently, gaining experience working with larger textiles was extremely helpful in learning how to approach condition assessing such objects.

I was fortunate enough to spend a day on the tapestry frame with Hazel, senior tapestry conservator at ZTC, who showed me the different tapestry stitches and talked me through the various stages of conserving a large tapestry. Due to the Covid-19 lockdown last spring, we had missed the tapestry block as part of the Textile Conservation programme at the University of Glasgow which would have introduced us to tapestry conservation. The experience with Hazel covered all the basics of tapestry conservation but I realised this type of conservation requires great skill and patience and years of experience! I am hoping to be able to gain more experience once I have graduated.

© Zenzie Tinker Conservation Ltd

In my last week, I helped wet clean a World War I uniform that had been involved in a leak while in storage and had subsequently got mouldy (see fig 4). It was an early start to ensure the wet cleaning could be completed in a day (a very important part of any wet cleaning treatment!). All the team helped with the various stages of sponging detergent, taking turns when our arms could sponge no more, blotting to pull out more soil and detergent, rinsing and finally carefully pinning out to ensure the uniform did not change dimensionally as a result of being wet cleaned.

The in-person placement demonstrated the importance of discussing projects, ideas and decisions which were a fundamental part of everyday work in the studio. These small conversations, which we have started to call ‘corridor conversations’ on the Textile Conservation programme, being the informal part of decisions and sharing of knowledge. These ‘corridor conversations’ have been difficult to maintain in the pandemic and something I missed when completing my summer placement virtually. Even by just being in the working environment of a conservation studio for a few weeks helps the development of skills and knowledge in conservation. Zenzie and her team made me feel very welcome throughout my time in Brighton, guiding me through their approaches as a private conservation studio. The experience of working in a conservation studio and being part of a team of conservators was invaluable and something I am very grateful for.

Thank you Zenzie Tinker and her wonderful team!