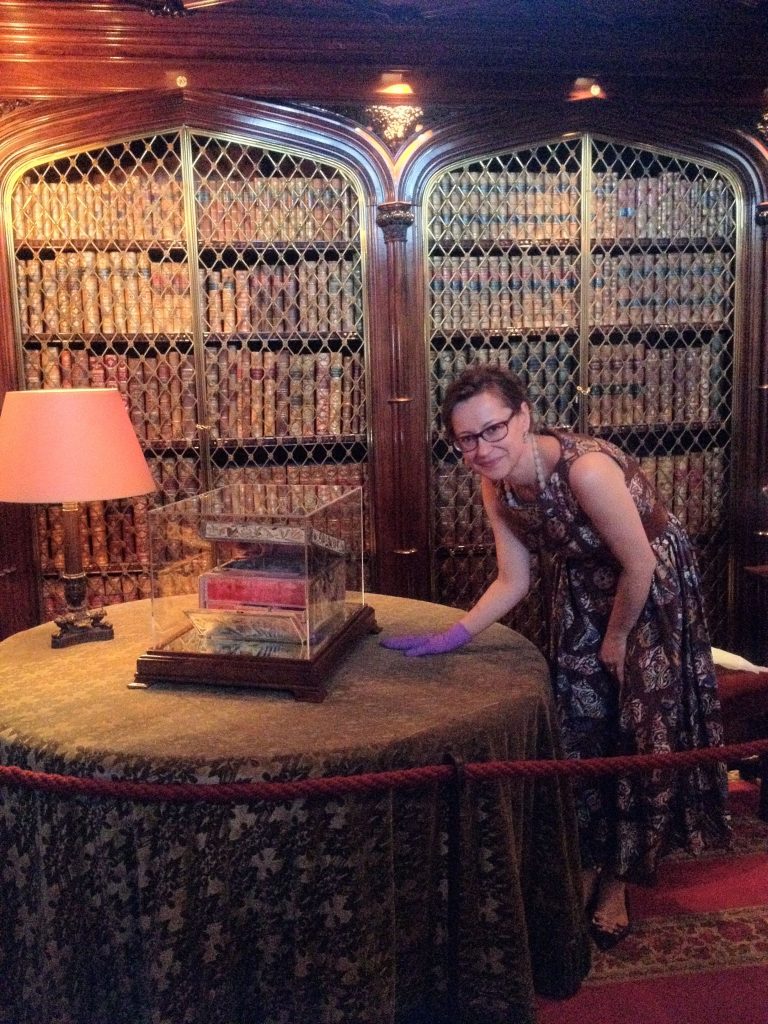

I remember noticing the exquisite 17th Century casket on my first walk through the castle. It was hidden away in the library, a beautiful suite of 19th C reading rooms furnished in crimson plush, polished wood and overflowing with the most amazing treasures of every type. The casket was squashed into a teeny tiny display case barely larger than than itself – it looked like a beautiful delicate prisoner in a small cell.

Some years later I was delighted to find myself trying to coax it out of the small display case without causing further damage and be assessing its conservation and display needs. Once released it was thrilling to be able to open up all the drawers and find the secret hidden compartments and imagine the lovers notes and jewels it probably contained. We know from research that similar caskets were used by girls and women from wealthy families for storing small personal items like jewellery, writing equipment, letter or needlework tools. They would often work the embroidered panels themselves from kits that when finished would be sent to a cabinet maker to be applied onto a wooden base. These kits were early examples of commercial embroidery enterprise.

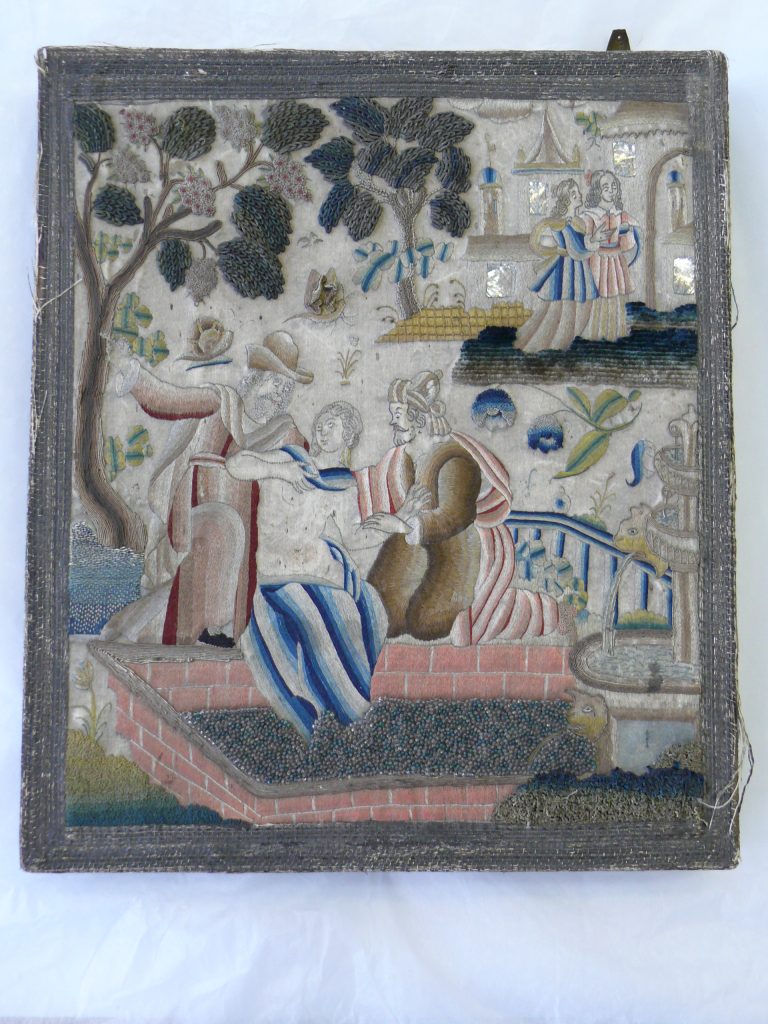

The Arundel Castle casket is made of cream silk satin lavishly embroidered with polychrome silk and metal threads depicting Jacobean scenes, possibly the story of David and Bathsheba. The scenes also incorporate metal braids, tiny pieces of mica and glass beads. The panels of embroidery are mounted over a wooden box with drawers and compartments some of which hinge with both metal and silk. The base of the main compartment is lined with a colourful printed paper of a lakeside scene with figures on horseback whilst the sides are fitted with mirror, reflecting back the printed scene in the base whenever the box is opened. Other compartments and drawers are lined with flocked silk velvet, plain weave pink silk and lilac paper tissue.

Due to its vulnerable and fragile condition it was decided that the object should be treated with very minimal intervention. We utilised tiny amounts of reversible adhesive for re-fixing loose metal braids and threads and some laid stitching where possible. (Stitching into something fragile that is already stuck to a wooden surface very reduces the conservator’s options). One of the embroidered panels was completely torn off and rather than cause further damage by repairing the metal hinges and reattaching them, we devised a hidden Perspex support to hold it in position. This decision gave the opportunity to support it semi open thus revealing to the visitor the drawer fronts beneath.

The main lid with its damaged metal hinges was carefully repaired and reattached but the detached, damaged silk hinge was too weak to re-use and so it was left resting in the main compartment. A new ribbon was made from custom dyed silk lined with Remay and attached inside the box using some pre-existing holes.

Very much part of the conservation was the design and making of a new display case with slightly more generous proportions that the previous one. A simple polished oak frame was constructed to reflect the Gothic Revival style of the Castle Library setting.

The client liked the idea of visitors being able to see inside the casket and get an impression of the many drawers and compartments so we came up with the idea of using mirror for the base of the case so that the embroidered underside of the semi open box flap could be seen. And enough space was planned around the casket this time for the lid to be left propped open. Unobtrusive supports were made from Perspex and UV filtered, non reflective Museum grade Perspex was used for the glazing of the case which lifts on and off and is secure with a simple lock.

This jewel of an object can now be seen and appreciated properly by the family and visitors to the castle and remains well protected for future generations to enjoy as well.