This bold and colourful military patchwork quilt is from Tunbridge Wells Museum and Art Gallery. It came to our studio for conservation before being loaned to Tate Britain for the recent British Folk Art exhibition. It then returned for another period of display back in Tunbridge Wells Museum.

Our brief was to minimally conserve the quilt and then to design and make a suitable display board. The board had to be designed to allow partial folding without compromising the safety of quilt thus allowing access back into the much smaller Tunbridge Wells Museum building. Geoffrey designed a clever hinged, lightweight grid support for a polycarbonate faced board that we padded and covered with display fabric and then stitched the quilt to.

During the 19th Century there was a real craze for quilting and although traditionally viewed as a female pastime soldiers were encouraged to take up quilt making and military quilts became extremely popular in Victorian Britain. This quilt was reputedly made by convalescing soldiers recovering from the horrors of the Crimean War of 1853–1856 but as these types of quilts were often known as Crimean quilts this might be a romanticised interpretation of its origins.

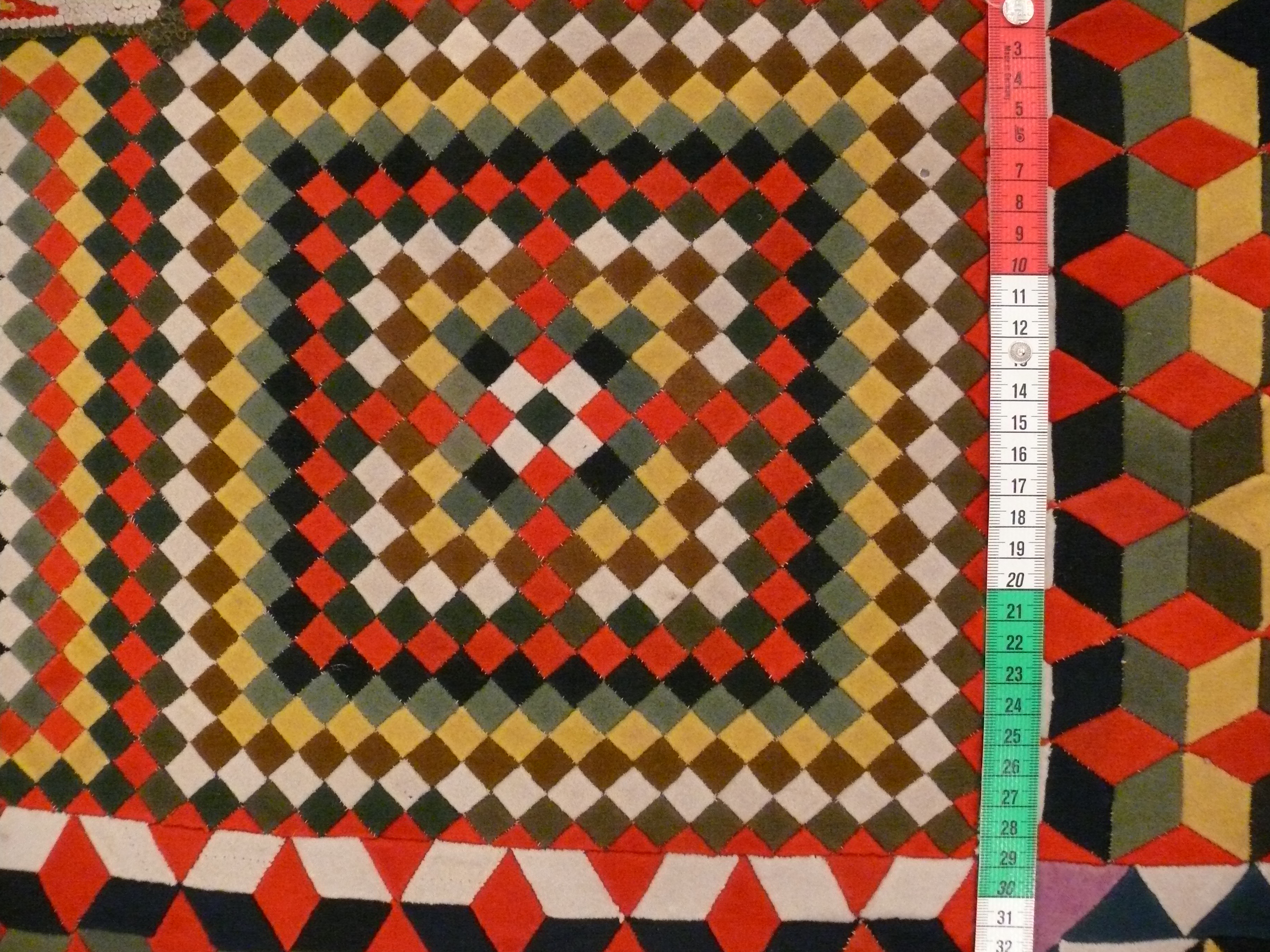

Constructed from thousands of small geometric shapes cut from differently coloured wool cloth used for military uniforms the quilt is exquisitely pieced and stitched by hand. Looking closely at the different army shades, you can see traces of their former use; old hemlines, stitch outlines left from jacket pockets and even buttonholes. Hazel who worked on the quilt marvelled at some of the bright colours in the patchwork. In particular she commented on the light purple, “if these quilts were made out of old bits of military uniform, you’ve got to wonder what sort uniforms were light lavender in colour?”. Lavender does seem to be an unusual choice of colour for the military however bright colours have been associated by historians with the military quilts made in late 19th Century India.

Apart from patching moth holes and repairing some of the structural stitching of the quilt the main challenge was mounting such a large, unevenly tensioned textile. With so many thousand hand-stitched seams the quilt was extremely undulated and wrinkled when laid flat. It also seemed to have become distorted from use as a table or sideboard covering.

We therefore carefully pinned the quilt to the display board from the centre of the design outwards, squaring and gently easing the quilt until it was as flat as possible without putting undue tension on the historic stitching. We followed the design of the quilt with our attachment stitching, working with curved needles and a reverse zig-zag stitch to reduce the pull of the new stitching.

It was very tough on the fingers manipulating the needle through the still thick military cloth – a fact we had in common with the original makers. An article about the Tate’s Folk Art exhibition from Artseer picks up on the physical endurance needed to create such quilts, “Here is a nineteenth century example of post-traumatic stress therapy, some 30,000 pieces of wool fabric in various army shades of red, green, black and yellow, stitched together with military precision and the physical effort necessary to sew through thick combat material. The design is bold, repetitive, orderly and, above all, masculine….”