I was first asked by the National Trust to assess the conservation needs of the curtains on the Onlsow State bed at Clandon Park in 2010. They were principally concerned about pieces of a strange plastic like film that were dropping out of the hems of the curtains. Very intrigued I discovered it was the residue from a failing past adhesive treatment and was instantly hooked!

As with many textile conservation projects it grew into a far larger project. The bed itself had become too fragile for the house team to clean at all as the many of the textile elements were unsound and the whole thing was extremely dusty. Clandon Park had been under the ownership of the National Trust since 1956 but the bed was not bought from the Earl of Onslow until 1977. It appears to have had little or no conservation in the intervening years and due to its condition had not been surface cleaned for about 15 years as the dust levels attested.

The bed and en suite furniture date from c1708-10, a rare survival of an embroidered state bed suite richly covered in silk and metal thread passementerie, lined with cream silk satin and with a cream silk satin quilted counterpane. Annabel Westman, noted furnishings historian has matched the Clandon passementerie to the 1711 state bed at Hatfield House with its fryars knots, crepe faggots and silk covered buttons. There is evidence that the Clandon bed was originally a flying tester or angel bed, foot posts were probably added for stability at some point and then replaced with painted metal scaffolding poles currently in place in the mid 1970’s. The embroidered curtains and upper valances also show evidence of alteration but much earlier on in the bed’s history, possibly even before the fabric was used on the bed. The bed embroidery may have been commissioned and then fashions changed before it was used prompting an alteration to the embroidery before it was applied to the bed. Sadly there do not appear to be any records of the past alterations; all we know is that the state bed suite was made for the previous house which was demolished in the 1730’s and it is assumed that these furnishings were moved to the new house in the middle part of the 18th century.

The curtains, upper valances and the counterpane were fully conserved in the studio whilst the rest of the bed was cleaned and minimally repaired in situ. We will focus just on the treatment of the curtains and their linings here.

After very careful surface cleaning using vacuum suction we dyed linen to patch support weak areas of the embroidered linen curtains. There were holes and weaknesses along the side edges of all the curtains from use. Loose and abraded embrodiery threads were sewn back down but there was little that could be done to conserve the black silk outline thread which was powdery to the touch. To reduce loss during handling we made padded handling and temporary storage boards.

All the curtain and valance passementerie was checked, surface cleaned and repaired using stitching. Loose elements were reattached and those silk covered buttons with their overlaid yellow silk decorative threads that had become worn were protected with dyed net.

View of curtain lining in situ

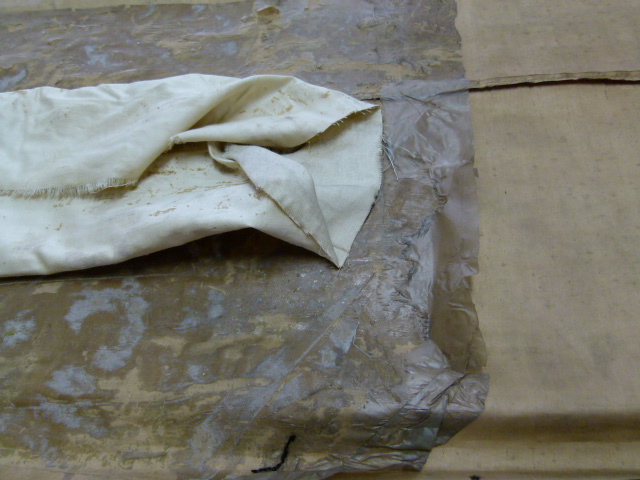

Detail showing unsightly failing patch

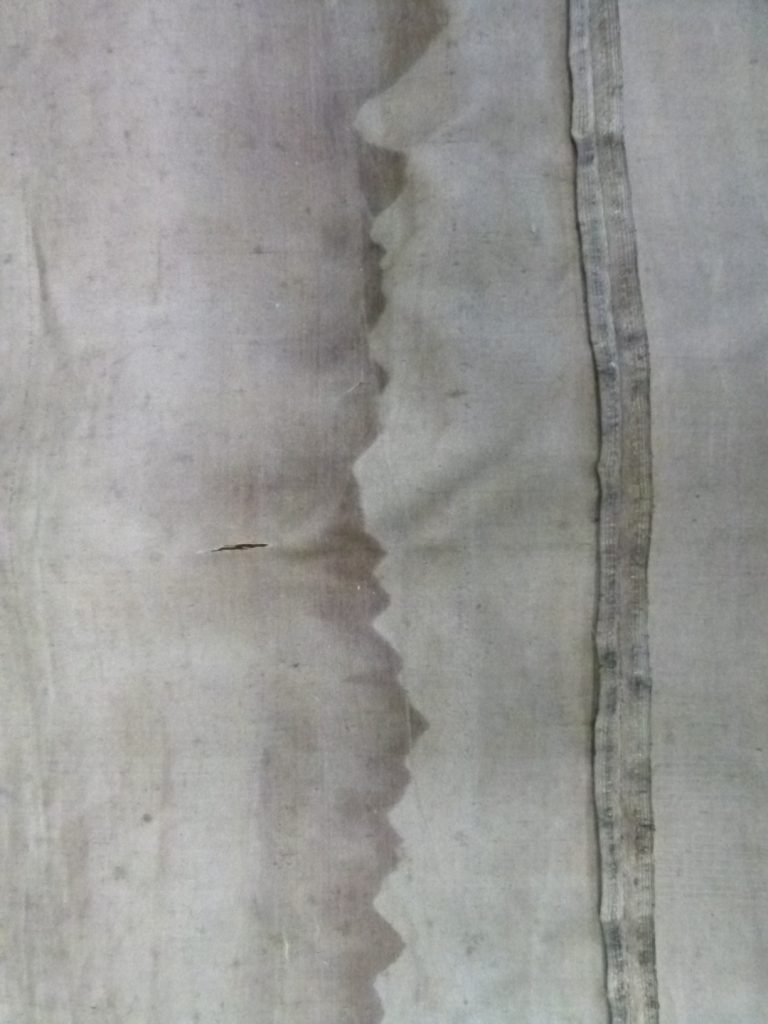

Water staining

The curtain linings were far less straight forwards to conserve than the embroidered curtains themselves. These had suffered both light and mechanical damage in stripes as is typical with curtains hanging gathered in the same position for years. They had also been badly water stained from a leak in the late 20th century and were very soiled and stiffened. At some point in the late 19th or early 20th century the linings had been repaired using an adhesive film. This was now failing, falling out in pieces, stiff and very unsightly. In some places it remained a distinct film and in other places it had soaked into the weave structure causing stains with glue brush marks still visible.

We had the adhesive identified as being a mixture of gutta percha (natural rubber), clay and wax but at that stage we drew a blank as to what type of adhesise that was and what it would have been designed for. But knowing the constituent parts of the adhesive was helpful in designing a solvent to aid in its removal. Much experimentation followed as we also needed to be able to flush out staining caused by the solvent but eventually we found a combination of chemicals and processes that worked and we managed to remove all the adhesive without damage to the fragile silk and then move on into wet cleaning.

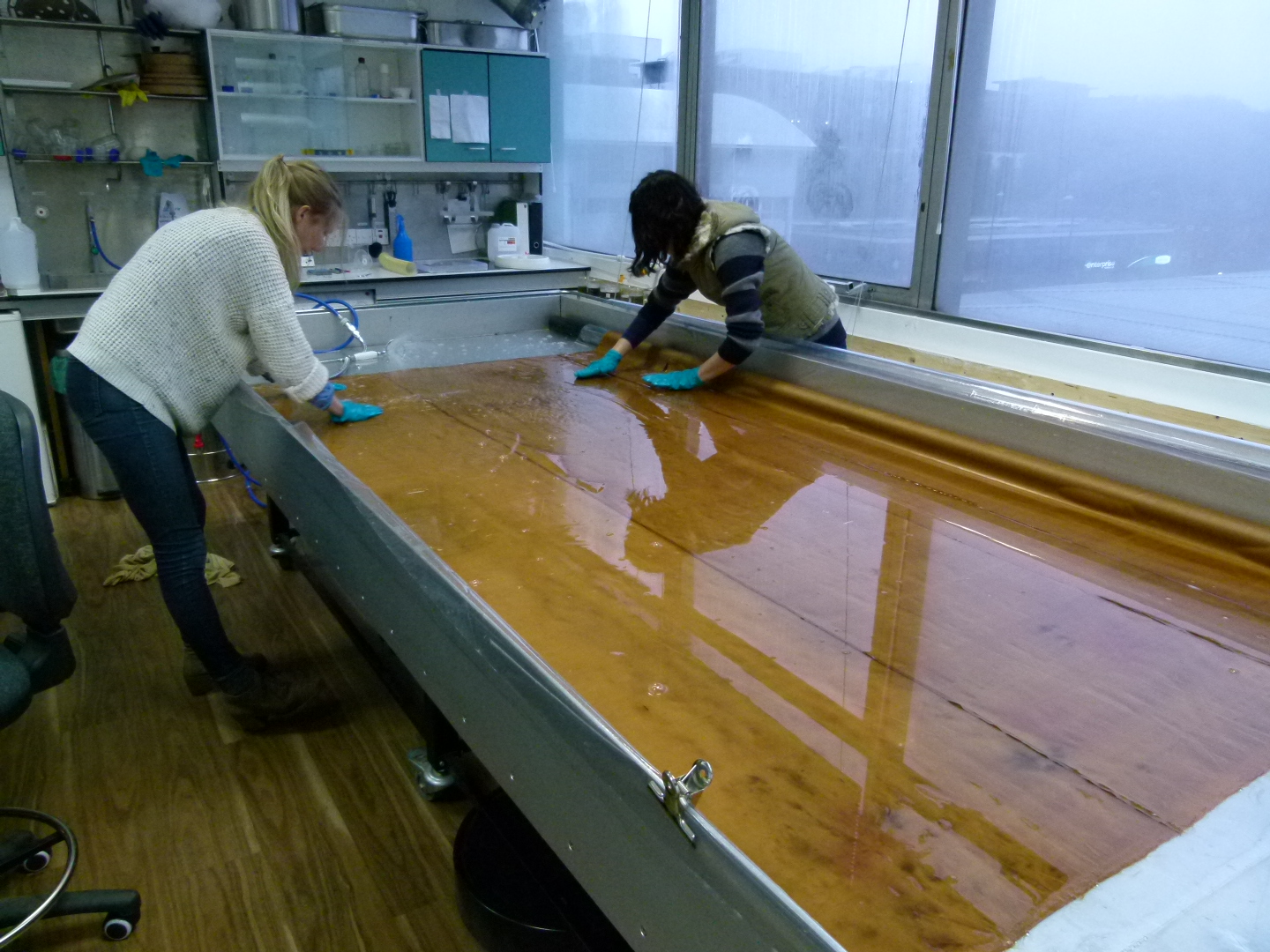

The four curtain linings were wet cleaned individually and were transformed by the process; the aqueous treatment brought softness and flexibility back to the satin linings and also restored their beautiful lustrous quality. And additonally all the staining caused by the adhesive and the water leaks was successfully removed .

After cleaning the next phase of support could commence, that of their support. Because of their fragmentary condition we elected to give each a full support on a layer of adhesive treated dyed silk crepeline which was then stitched through to a full support of dyed silk for strength. The adhesive and stitched supports were added following the original construction. Dyed net overlays were also added to the most damaged widths of fabric prior to the linings being reinstated in the embroidered curtains. The conservation of the four curtains took about 1600 hours to complete.

Due to the still fragile nature of the curtains they were packed into glazed storage crates and displayed in the state bedroom at Clandon in March 2013 whilst the NT curators began the process of researching the original layout of the state bedroom with a view to possibly reinstating that floor plan. Nearing the point that the bed would be moved we went and packed the displayed and now fully conserved counterpane into the crate with the curtains.

Tragically on 29 April 2015 a devastating fire raged through Clandon Park. Heroic fire crew and house staff were able to rescue the crates containing the curtains and counterpane as well as all but one of the ensuite furniture while the house burnt. The next day there was hope of rescuing the wet bed but soon afterwards the floors above the state bedroom collapsed onto the bed. It then remained crushed and wet for about 18 months while the skeleton of the house was made safe and excavations could begin.

See our Conservation Story, ‘Clandon one year on’ for more information about the extraordinary retrieval of the state bed.

In 2019 Zenzie was one of the specialist team invited to discuss the future of the remains of the Clandon state bed. We await their decision with very great interest and hope one day to see this extraordinary object restored once more to its former glory.

See Annabel Westman’s wonderful book, ‘Fringe Frog & Tassel, The art of the Trimmings-Maker in Interior Decoration’, where the Clandon bed passementerie featured a number of times.